Musing No 8

Thinking about writing, the lifecycles of murder files and scenes of crime material

I’m writing Murder in the Archives and this is one reason why I’ve joined Substack—I’d like to drum up some interest in my book which is due for publication in July. But I’m also using the platform as a writing ‘gym’ to think through ideas, improve my writing speed and fluency (because I’m a very slow and hesitant writer) and gain in confidence. And for this, Substack has been great in freeing up inhibitions and increasing that flow of thought from brain to fingers to keyboard.

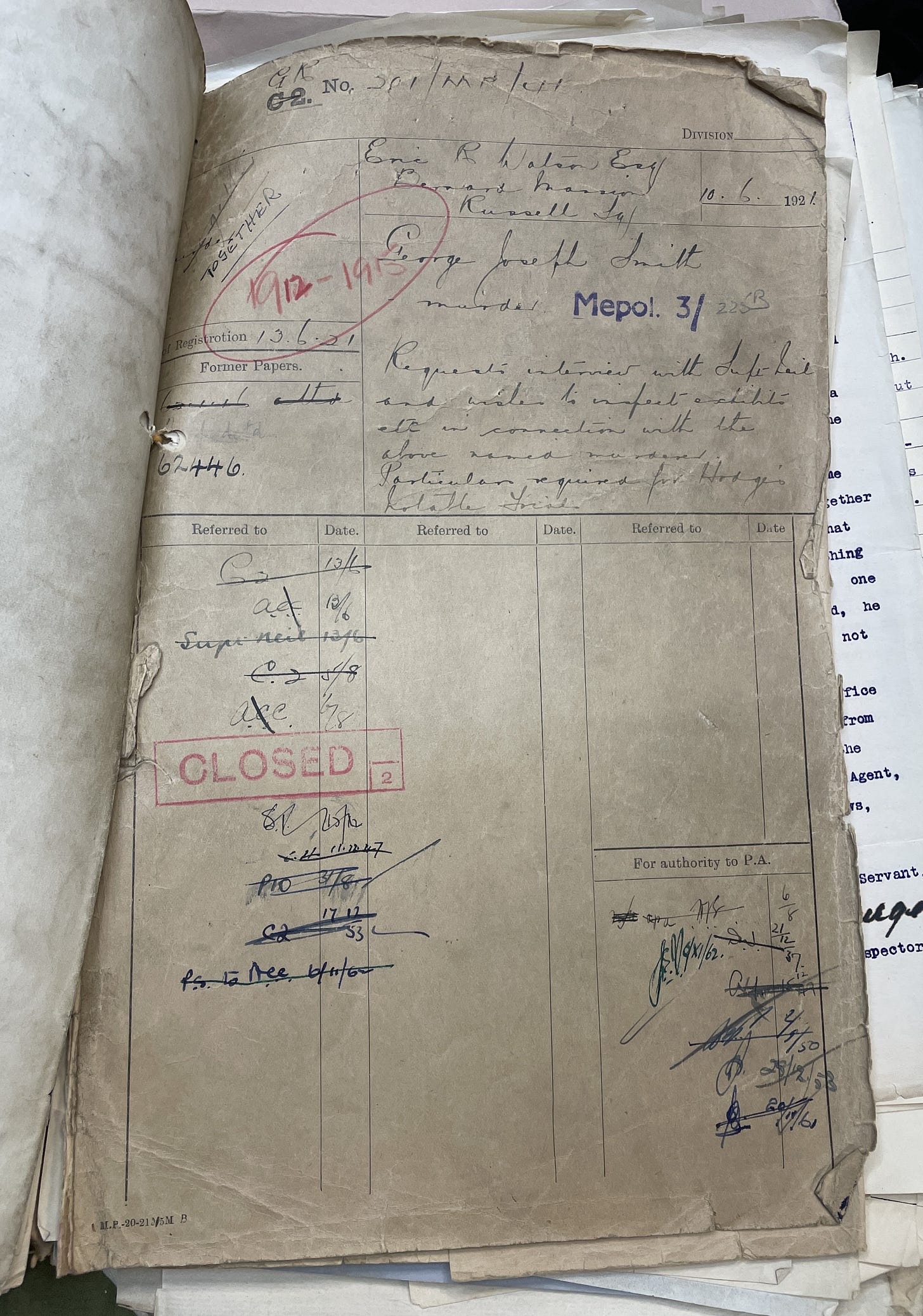

Murder in the archives is now on Draft No 10 which, at present, consists of a very scrappy Prologue, an even scrappier Epilogue—because I’ll leave both until the end— and four meaty chapters, each divided into three parts. The four chapters follow the stories of regional police force-created murder investigation files and the point of the book is that rather than viewing these files simply as vessels for information, they are treated as objects with their own stories and material culture. Chapter One, then, examines their makers—the detective—and the culture into which the files were conceived. Chapter Two considers how and why some murder files may leave the obscure world of C.I.D. and find their way into the public domain and local record offices; and here memory and emotion rather than any formal records management practices play a key role together with the arrival of DNA and cold case reviews. With their zenith of public appearances occurring between the 1910s and 1980s, Chapter Three, then, considers their disappearance from public life—the huge shifts in policing culture and increasing fear of keeping information.

At present I’m reworking and re-reworking the final chapter which is set in the archive and evaluates the place of these complex and difficult files—their interpretation and their shift from highly confidential and working records to a cultural object with expectations around access. The chapter also considers their physicality and how this speaks of circulation, technologies, rank, events such as war which made resources such as paper rare.

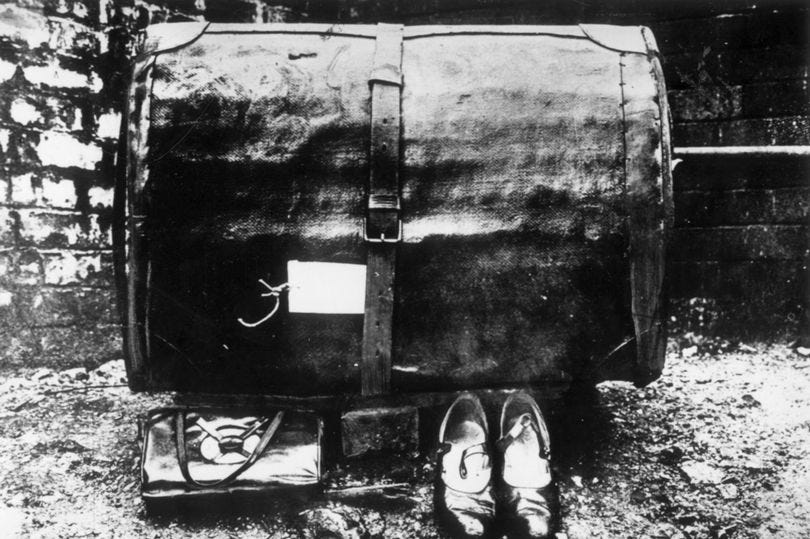

And last, the chapter explores lists of exhibits often contained in the murder file which refer to three-dimensional objects in the form of collected evidence from the crime scene, and some of this evidence has survived in police museum collections. The trunk which contained the dismembered body of Minnie Alice Bonati which was deposited by her killer, John Robinson, in the left luggage office at Charing Cross railway station in 1927 is now at the Metropolitan Police’s crime museum. One of the “Brides in the bath” baths used by George Smith to drown his three wives between 1912 and 1914 is now held at the National Justice Museum in Nottingham—though not displayed for reasons of sensitivity. However, a second bath in which Dr Buck Ruxton dismembered the bodies of both his common law wife and maid in 1935 was first used as a horse water trough by the local constabulary before eventually finding its way into a fully reconstructed bathroom display at Lancashire Police Museum. I argue in Chapter Four that such objects need to be treated and interpreted with care and sensitivity.